Post-Grant Report

2016 Post-Grant Annual Report

Authors

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Senior Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

2016 marked the fourth anniversary of the America Invents Act (AIA)

The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) was once again the forum of choice for challenging patentability of claims, surpassing the Eastern District of Texas as the #1 venue for patent disputes. 2016 also marked the launch of the PTAB Bar Association, the first national bar association of its kind to form in more than 30 years. The PTAB Bar Association intends to establish best practices for the unique skills required to practice before the PTAB. More than 45 law firms joined to form the association, which will host its inaugural conference in 2017.

Fish’s 2016 Post-Grant Report examines significant case law and decisions before the PTAB and the Federal Circuit as well as trends and statistics from the past year. It also reviews the new rules for post-grant proceedings and takes a closer look at the biopharma industry and its use of inter partes review in patent disputes.

Fish & Richardson is one of the most active firms at the PTAB and is the most active firm representing petitioners.

New Rules for Post-Grant

Effective May 2, 2016, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) made some changes to its rules of practice before the PTAB and declined to make other suggested changes. This second round of changes is in addition to the “quick fix” changes made in 2015. Here are the new rules, roughly in order of significance.

Testimonial Evidence in a Preliminary Response

Probably the most significant new rule permits patent owners to submit new expert declarations and testimonial evidence with their preliminary response.

Petitioners have always been allowed to include testimonial evidence, such as expert declarations, with their petition. However, patent owners had been precluded from submitting such testimonial evidence with their preliminary response. Patent owners could submit such evidence only with their full response, after the PTAB instituted a proceeding. As a result, patent owners sometimes felt limited in their ability to fully present arguments and distinctions that might have prevented institution.

Patent owners are now permitted to file expert reports and other new testimonial evidence with their preliminary response. According to the USPTO, this change is intended to balance the institution procedure. However, the amended rules expressly provide that any genuine issue of material fact will be viewed in the light most favorable to the petitioner for the purpose of deciding whether to institute the review. Accordingly, such declarations should focus on issues that may not raise a factual dispute, such as the broadest reasonable interpretation of a claim limitation (ultimately a legal distinction), a factual issue that is not addressed in the petition, or evidence antedating an alleged prior art reference. Petitioners may request a reply to address issues raised in such declarations; however, so far replies have rarely been granted.

.jpg)

Revised Size Limits

An amendment to Rule 42.24 changes the size limits from page limits to word count limits for petitions, patent owner preliminary responses, patent owner responses after institution, and petitioner replies. Also, certain mandatory notices are now excluded from the limits. Application of a word limit, instead of a page limit, allows practitioners to use larger images and less-crowded text, rather than try to shrink it to satisfy a page limit.

PTAB Sanction Authority & Procedure

Although the USPTO already believed that the PTAB had the authority to sanction bad behavior, the amended rules clarify that authority and the procedure. Similar to Rule 11 in the federal courts, the amended Rule 42.11 requires that all filings in PTAB proceedings be signed, that the signature be treated as a certification that the paper is not being presented for any improper purpose, and that there is a basis for legal and factual contentions and denials. Rule 42.11(d) permits the PTAB to impose appropriate sanctions for violations. The rules give the offending party an opportunity to correct, with no sanction if the challenged paper, claim, defense, contention, or denial is withdrawn or corrected. The USPTO specifically declined to give an example of what might be an “improper purpose” in filing a petition, but stated that the USPTO does not expect to use the procedure often.

Claim Construction for Expiring Patents

The USPTO traditionally applies the broadest reasonable interpretation standard to claim construction, because the patent owner can amend a given claim should it disagree with how that claim is being construed. A new rule, however, allows parties to “request a district court-type claim construction” upon certification that the challenged patent will expire within 18 months of a filing date being accorded to the petition. The change attempts to address the situation where impending patent expiration effectively negates any value of amending claims.

No Change to Claim Amendments

The USPTO declined to make any formal rule change regarding claim amendments, instead preferring to develop the law by identifying certain decisions as precedential. Amendments are a hot-button issue for practitioners, as some argue amendments should be easier to make while others argue that amendments should be eliminated from these proceedings altogether. In the end, the right to amend remains as it was–a possible but challenging task.

Service of Demonstratives

The new rules also require earlier service of demonstrative exhibits before the oral hearing. This change will provide additional time to consider disputes over proper demonstratives.

Conclusion

These rule changes can have an important impact in some cases, and they are all important to know. However, they do not substantially change practice before the PTAB, which will continue to be an attractive forum for parties seeking to have patent validity reviewed by three administrative patent judges, instead of a jury, within a relatively short time.

Life Sciences at the PTAB

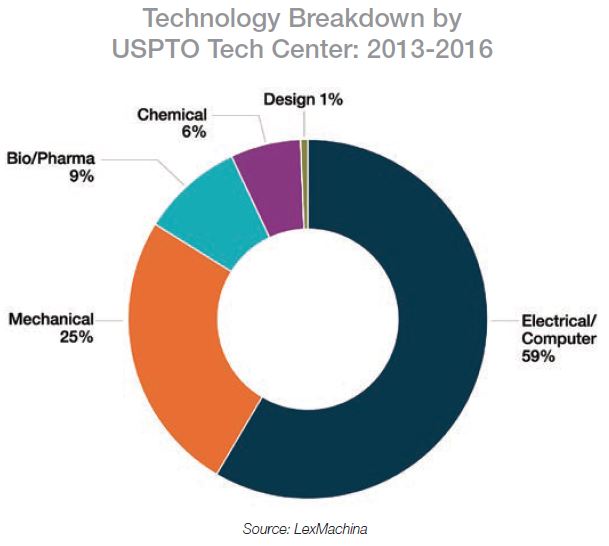

Although the overall number of post-grant petitions filed has started to plateau, the percentage of biopharma petitions, which we define as petitions involving Group 1600 patents, continues to grow. In FY 2016, biopharma petitions accounted for 13% of all petitions filed. This compares with 9% in FY 2015 and 6% in FY 2014. The vast majority of petitions are IPR petitions. Institution rates are under 60%.

In 2016, we saw biopharma petitions expand from small molecules to biologics and biosimilars. Brand-name biologics that were the subject of IPR petitions included HUMIRA®, ORENCIA®, ENBREL®, RITUXAN®, and TYSABRI®. In some cases, the IPR process may form part of a “freedom to operate” strategy to clear out patents in the early stages of biosimilar development so that they do not become impediments when a biosimilar application is filed.

Hedge fund manager Kyle Bass has continued to be active in the biopharma sector. He currently has an institution rate of almost 57%. Nine of his IPR petitions have gone to final written decision, with Bass succeeding in eight of them. In one particularly notable decision, Bass successfully convinced the PTAB that the claims of a Shire/NPS formulation patent covering GATTEX®, a drug for treating short bowel syndrome, were unpatentable.

Looking ahead to 2017, we forecast continued growth of post-grant activity in the biopharma sector, particularly in the biologics area.

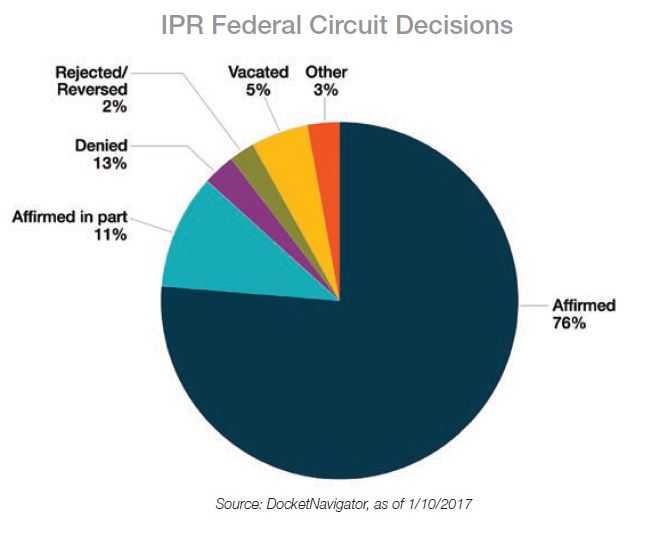

PTAB Appeals

The Federal Circuit issues about 100 precedential IP decisions each year. A fast-growing portion of that docket involves PTAB appeals, especially from post-grant proceedings.

The main post-grant issues in 2016 grew out of two points affirmed by the Supreme Court in Cuozzo Speed Technologies, LLC v. Lee, 579 U.S. __ (2016). First, the Supreme Court decided that the PTAB may apply a broadest reasonable interpretation (BRI) standard for claim construction, rather than the Phillips standard that applies in litigation. The Court, however, did not explain how that standard is to be applied, which could be important because there are real questions about where the BRI standard departs from the Phillips standard. The concern for parties moving forward should be to obtain greater guidance from the Federal Circuit on the differences between BRI constructions and Phillips constructions.

The second Cuozzo issue stemmed from various Federal Circuit holdings that PTAB decisions made at institution are, for the most part, unreviewable on appeal. The Supreme Court agreed, though noting that the Federal Circuit might have review in extreme cases, such as when a constitutional right is implicated. So it is business as usual for parties in post-grant proceedings—though we are now trying to determine what rare situations are extreme enough to merit reviewability. Some members of the Federal Circuit provided a clue recently in the non-precedential Click-to-Call [CTC] Technologies, LP v. Oracle Corp., 2016 WL 6803054 (Fed. Cir. Nov. 17, 2016). The panel there had initially dismissed CTC’s appeal, which argued that the PTAB should not have instituted an IPR because it was filed too late, and the Supreme Court vacated in light of Cuozzo. On remand, CTC argued that Cuozzo had implicitly overruled the Federal Circuit’s prior Achates decision, which had held unreviewable a PTAB decision about whether an IPR had been timely filed. CTC argued that such a decision was not closely related to the institution decision and was thus carved out in Cuozzo. The Federal Circuit disagreed in a per curiam opinion. Judge O’Malley’s concurrence explained that a filed-too-late situation is analogous to an example the Cuozzo Court identified as being something a party could appeal. And Judge Taranto emphasized that the Cuozzo Court could have blocked all review and did not, so that the Federal Circuit should sit en banc to clear things up. These opinions suggest that at least some of the members of the Federal Circuit are open to judicial review of procedural actions by the PTAB at institution even if the same judges would continue to block review of merits determinations like anticipation and obviousness. See also In re Magnum Oil Tool Int’l, Ltd., 829 F.3d 1364 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (Federal Circuit can consider issues ruled on in Final Written Decision even if they were touched on in an Institution Decision); Harmonic Inc. v. Avid Tech., Inc., 815 F.3d 1356 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (affirming that PTAB did not have to consider bases for rejection that it had found redundant at institution, even though it later found that the art on which it instituted IPR did not invalidate the claims).

The other most important post-grant issue that the Federal Circuit discussed this year was the amount of reasoning the PTAB must include in its opinions. The court has said outside post-grant that the PTAB cannot just fill gaps with its own experience when the evidence is lacking, but it had not applied the standard for post-grant matters. That changed in a non-precedential opinion in Cutsforth, Inc. v. MotivePower, Inc., 636 F. App’x 575 (Fed. Cir. 2016), where a panel held that The Board failed by explaining the parties’ respective arguments, explaining why it rejected one party’s arguments, but not explaining why it accepted the other party’s arguments. The court more recently made a similar statement precedentially in In re NuVasive, Inc., 841 F.3d 966 (Fed. Cir. 2016). In reasoning that the PTAB did not explain why there was a motivation to combine the prior art references, NuVasive reviews the legal and policy reasons why the PTAB must provide findings to enable appellate review, and notes that: “it is not adequate to summarize and reject arguments without explaining why the PTAB accepts the prevailing argument.” And merely citing to common sense will often not suffice. See also Arendi S.A.R.L. v. Apple Inc., 832 F.3d 1355 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (when “common sense” is used against something other than a peripheral limitation, “it must … be supported by evidence and a reasoned explanation.”). These decisions are important because they ensure that the PTO provides full service under agency law, and parties and the Federal Circuit can understand why they got a particular result from the PTAB (and whether that result is right or wrong).

In contrast, the court held in In re Warsaw Orthopedics, 832 F.3d 1327 (Fed. Cir. 2016), that the PTAB does not have to find the exact claim limitations in any particular prior art reference, and can instead make logical adjustments to the art. In the particular case, the claims recited certain dimensions for spinal implants, and substantial evidence supported the Board’s obviousness conclusion. (The court did vacate on one claim, though, because the Board had not adequately explained itself.)

On another procedural issue, the question was whether post-grant appeals should receive a “clear error” standard of review rather than the more deferential “substantial evidence” standard that the Federal Circuit now applies. In Merck & Cie v. Gnosis, S.P.A., 820 F.3d 432 (Fed. Cir. 2016) and South Alabama Medical Science Foundation v. Gnosis S.P.A., 818 F.3d 1380 (Fed. Cir. Apr. 26, 2016), the court denied en banc petitions that sought to change the standard. Judge O’Malley concurred in the denial (joined by Judges Wallach and Stoll), noting that in her opinion, the substantial evidence standard is “inconsistent with the purpose and content of the AIA,” but that the Federal Circuit was bound to apply it by Dickinson v. Zurko, 527 U.S. 150 (1999). Judge Newman dissented alone and had no such qualms about not following Zurko, because the AIA post-dates Zurko and it created a new system, so she would change the standard of review to now provide a litigation-like standard for litigation-like post-grant proceedings.

The Federal Circuit also killed efforts this year to challenge other underlying post-grant processes. First, in Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc. v. Covidien LP, 812 F.3d 1023 (Fed. Cir. 2016), the court ruled that there was nothing wrong with the PTO using the same panel of judges to institute a post-grant proceeding and to make the final decision in the proceeding. The Federal Circuit majority found no constitutional violation and refused to infer that, because the statute says the director should institute a proceeding and the Board should decide the proceeding, the Director could not delegate the institution step to the Board. Judge Newman dissented under her belief that the statute made a clear distinction in responsibilities between the Director and the Board, which blocked the Director’s delegation. In MCM Portfolio LLC v. Hewlett-Packard Co., 812 F.3d 1284 (Fed. Cir. 2015), the court rejected the argument that IPR is unconstitutional because Article III of the Constitution and the Seventh Amendment reserve to courts and juries the ability to revoke an issued patent. People say “go big or go home,” but it seems the parties that go big in their post-grant arguments are also being sent home. But more practically, if you push an argument that would upset thousands of administrative proceedings, your argument had better be perfect or you will lose.

Finally, in the area of CBM proceedings, the Federal Circuit indicated that the Board was applying a too-inclusive standard for determining whether a patent qualified as a CBM patent in Unwired Planet, LLC v. Google, Inc., – F.3d –, 2016 WL 6832978 (Fed. Cir. Nov. 21, 2016). The invention was a system that allowed a mobile device users to limit how much of their location information was shared over a network. The Federal Circuit faulted the PTAB for applying a standard for CBM that was satisfied if the invention was merely “incidental or complementary to” other operations used in the practice, administration, or management of a financial product or service. The court focused on the “incidental/complementary” language—noting that a closer connection was necessary—and did not otherwise criticize the PTAB’s rules or rulings.

Post-Grant Review Proceedings Gaining Momentum

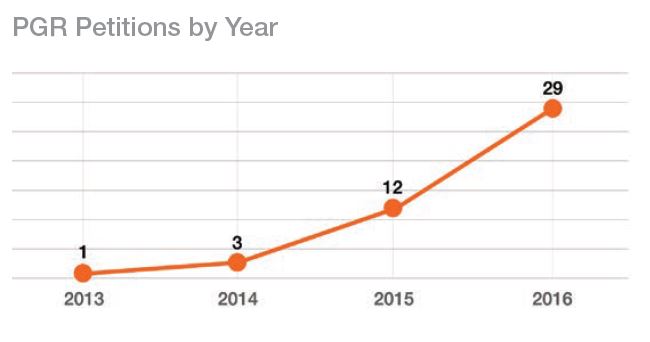

As the number of post AIA patents has grown, so has the number of post-grant review (“PGR”) filings. Whether the number of post- grant review filings is growing proportionately to the number of AIA patents though, it may be too soon to tell. However, it is clear that current PGR filings are, for the most part, taking advantage of the unique invalidity bases available only in PGR.

In 2016 there were 29 new PGR filings, as compared to 12 in 2015, and only four in the two years prior. Thus, while post-grant reviews are still rare (only 45 have been filed since inception), the number of new filings is increasing rapidly. As nearly all new patent grants are now PGR eligible, the number of new PGR filings will likely continue to increase, but at a more measured rate.

Unlike other manners of challenging patents at the Patent Office, PGR allows validity challenges on any statutory basis and can be filed within nine months of issuance. But, this versatility comes at a cost. PGR’s onerous estoppel extends to all basis of invalidity, and PGR has a higher threshold for institution (“more likely than not” versus IPR’s “reasonable likelihood”). These weighty considerations cause some Petitioners to shy away from PGR challenges. Yet, for some, the balance has weighed in favor of filing PGR.

A majority of the filings have been against biotech, pharmaceutical, and chemical technology patents, with mechanical technology patents a far second. Compare this to IPR, where the vast majority of filings are in computer architecture and software technologies. Nearly three quarters of the PGR filings involved statutory subject matter challenges (i.e. § 101) or enablement/written description challenges (i.e. § 112). While nearly all of these challenges included a prior art basis, the challenges employed PGR, presumably, because § 101 and § 112 basis would not otherwise be reachable in biopharma and mechanical technologies, which are unlikely to be CBM eligible. When prior art bases appeared to be the focus of the PGR challenge, there was more to the filing. For example, some PGR filings were second or third petitions related to other petitions with § 101 and § 112 challenges, and some were pressing forms of prior art unusable in other challenges, such as evidence of on sale or public use. Finally, a few PGR petitions were filed against design patents, challenging ornamentality of the design.

As the value of the newest granted patents becomes more apparent, when does it make sense to employ PGR? PGR may factor more heavily when immediacy of a patent office challenge filing is paramount. For example, if a newly granted patent is immediately enforced, because a PGR can be filed within nine months of issuance, a PGR may be the only patent office challenge that can be filed in time to factor against a preliminary injunction or to leverage into a stay. In certain “rocket dockets,” a PGR filing may be necessary to win the race to finality. Even when immediacy of the challenge is less important, the versatility of PGR, allowing any statutory basis of invalidity, may outweigh its negatives. For example, the Patent Office is often a more sophisticated venue on issues of enablement and written description than a district court. Thus, for non-CBM eligible patents, PGR is the only way to try these issues before the Patent Office. The need to employ PGR for statutory subject matter challenges, though, may be declining, given that now PGR-eligible patents were prosecuted after the Mayo, Myriad and Alice statutory subject matter cases.

Only time will tell how quickly the number of PGR filings will grow. However, the few that have been filed illustrate that PGR is a useful tool given the right circumstances.

The opinions expressed are those of the authors on the date noted above and do not necessarily reflect the views of Fish & Richardson P.C., any other of its lawyers, its clients, or any of its or their respective affiliates. This post is for general information purposes only and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice. No attorney-client relationship is formed.