Article

Eleven Ways the PREVAIL Act Would Alter PTAB Practice

Law360

Authors

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

Principals Jeffrey Shneidman and Jacqueline Tio have authored an article for Law360's Expert Analysis discussing a new Congressional bill that, if passed, would significantly change post-grant practice at the U.S. Patent Trial and Appeal Board.

Read the full article on Law360.

A new set of congressional bills were recently proposed that — if passed as the Promoting and Respecting Economically Vital American Innovation Leadership Act — would change post-grant practice before the U.S. Patent Trial and Appeal Board in several key ways.

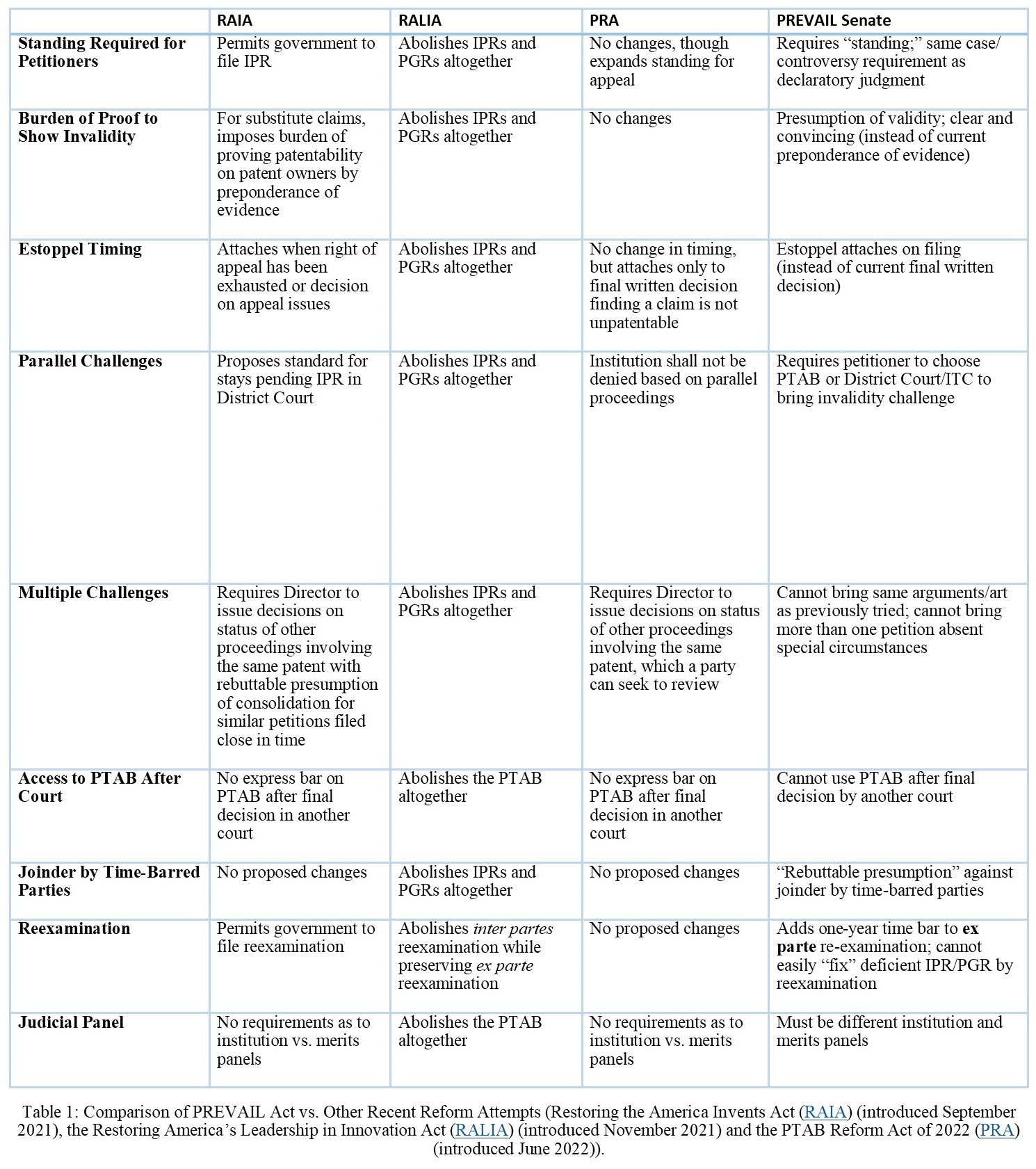

The PREVAIL Act comes on the heels of several other major legislative proposals in the last few years to change Patent Trial and Appeal Board practice, including the Restoring the America Invents Act, introduced in September 2021; the Restoring America's Leadership in Innovation Act, introduced in November 2021; and the PTAB Reform Act, introduced in June 2022.

This article summarizes what the PREVAIL Act would change about PTAB practice, and how the proposals in this act compare to prior legislative attempts to change PTAB procedures that have been brought forth over the last few years.

How The PREVAIL Act Would Change PTAB Practice

The proposed changes in both the U.S. Senate version and U.S. House versions of the PREVAIL Act would affect PTAB post-grant practice, especially as to inter partes review and post-grant review, in several potentially dramatic ways.

Because the IPR procedure under Title 35 of the U.S. Code, Section 318 is a vastly more popular vehicle for challenging patents as compared to the post-grant review procedure under Title 35 of the U.S. Code, Section 321, we explain these proposed changes in terms of IPR practice, but consider that the PREVAIL Act proposes similar changes for post-grant review practice.

It is worth noting however, that IPR is limited to "ground[s] that could be raised under section 102 or 103 and only on the basis of prior art consisting of patents or printed publications," while post-grant review does not have such a limitation, under Title 35 of the

U.S. Code, Section 311(b). As such, the limits of the PREVAIL Act discussed below as to printed publications do not apply to the proposed changes.

Adds a Standing Requirement to Bring an IPR Petition

Currently, anyone can bring an IPR challenge to a patent at the PTAB, even without a case or controversy existing between the petitioner and the patent owner such as what would be required for entrance into an Article III court — e.g., to bring a declaratory judgment action of invalidity.

Under the existing rules, parties can file IPRs even if they do not have a legal dispute with the patent owner, or more typically, can file an IPR prospectively if they believe a patent holder may threaten them later — e.g., a technique used by entities that wish to test patent validity early in a costly development process, such as in typical drug development.

In addition, under current law, third party collective organizations can bring IPR challenges for the benefit of their members.

The PREVAIL Act would change the rules to limit PTAB petitioners only to those entities, or their real parties in interest, that have been sued or threatened with a patent infringement suit. This change generally matches the standing requirement needed to bring a declaratory judgment action in federal court.

Presumption of Validity and Standard of Review

Under current law, a petitioner seeking to invalidate a patent claim must prove invalidity by a preponderance of the evidence, which is a lower standard than the clear and convincing burden that must be met in federal district court and the International Trade Commission.

The PREVAIL Act would modify Title 35 of the U.S. Code, Section 316(e) to impose the presumption of validity applicable in district court to the PTAB, and also would raise the bar at the PTAB to require a showing of invalidity by "clear and convincing" evidence, matching district courts.

For substitute claims first offered within a PTAB proceeding, however, the PREVAIL Act offers a carveout, with provisions that direct the PTAB to apply the current preponderance of the evidence standard to evaluate a petitioner's invalidity attacks on the proposed substitute claims.

Estoppel Timing

It is typical for a defendant in a district court litigation to become a petitioner in an IPR proceeding seeking to challenge an asserted patent on which the party is being sued.

Under current law, if a PTAB petitioner files an IPR and the proceeding progresses all the way to final written decision — i.e., approximately 18 months after the petition is filed — the petitioner is estopped from asserting any invalidity ground in related litigation that they raised or reasonably could have raised in the IPR.

The PREVAIL Act would change the timing of when this estoppel kicks in, making estoppel attach as soon as a petition is filed.

As a corollary, early settlement of an IPR prior to a final written decision would no longer impact estoppel. Under current law, a termination due to party settlement does not trigger the estoppel bar because the matter does not reach a final written decision.

Closing a Dual-Challenge Opportunity

Currently, a defendant who is sued in district court or a respondent in the ITC can raise invalidity — either as a counterclaim, in district court, or as an affirmative defense, in district court or the ITC — and still later bring an IPR challenge at the PTAB based on patents or printed publications.

The PREVAIL Act closes off this dual-challenge opportunity.

The PREVAIL Act also clarifies that a would-be petitioner at the PTAB is not disadvantaged from initially raising such defenses or counterclaims in district court or the ITC; rather, if an IPR is later filed and instituted, the petitioner would need to drop any parallel invalidity case based on patents or printed publications.

As to IPR, this provision affects only what is set out and does not address the full scope of grounds that could not have been raised before the PTAB, such as a PTAB challenge based on so-called system art or challenges under Title 35 of the U.S. Code, Section 101 or 112.

Expanding Estoppel to ITC Proceedings, Tightening Affirmative Defense Estoppel

Under the PREVAIL Act, just as a would-be petitioner must choose their forum for challenging validity based on patents or printed publications — see above — a would-be petitioner cannot litigate validity on these grounds in district court or the ITC, and then if they do not prevail, try again at the PTAB.

Under current rules, neither a defendant's affirmative defense in district court nor the ITC starts the one-year time bar in which a defendant may seek IPR. Similarly, being named as a respondent at the ITC without being named in district court does not start the one-year clock.

The PREVAIL Act would effectively impose a time bar in both scenarios, as a rule that once a district court or the ITC reaches a final judgment as to the validity of a patent claim on grounds that could have been considered in IPR, a would-be petitioner cannot bring or maintain an IPR proceeding on that same patent claim.

Limits Challenges Against the Same Patent

Under current law, there is no statutory limit precluding multiple petitions against the same patent. While PTAB panels acting on behalf of the director have the power of discretionary denial, there are cases where multiple petitions against the same patent have been allowed.

As to repeat arguments and prior art, the PREVAIL Act would require the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office to "reject any petition that presents prior art or an argument that is the same or substantially the same as prior art or an argument that previously was presented to the Office," absent exceptional circumstances.

The PREVAIL Act would require the director to set forth regulations laying out the standards for demonstrating such exceptional circumstances.

As to a repeat petitioner, the PREVAIL Act would prescribe that a petitioner can file only a single petition against a patent, absent special circumstances.

One challenge for petitioners under the existing PTAB structure is the 14,000-word limit for petitions dictated by Title 37 of the Code of Federal Regulation, Section 42.24.

Petitioners challenging patents with larger claim sets or patents that involve complex subject matter currently may seek to use multiple petitions in view of the 14,000-word limit.

The PREVAIL Act has attracted some early criticism by not accounting for claim or subject matter complexity while restricting challenges to a single petition.

Creates a Rebuttable Presumption Against Joinder if Joinder Would Violate the One-Year Filing Bar

Under current law, a person who is barred from bringing an IPR petition because of a time bar — e.g., because they were sued more than a year prior to bringing a petition — may nonetheless join a third party's petition brought by another party without being restricted by the time bar under Title 35 of the U.S. Code, Section 315(c).

The PREVAIL Act would create a rebuttable presumption against such joinder. Moreover, such a person who is otherwise time-barred would be exposed to a situation where the lead petitioner settles out of their portion of the case.

Commentators have questioned whether this change, which would seem to require termination of proceedings addressing patents for which a reasonable expectation of unpatentability has been endorsed, is consistent with the policy goals that inspired the introduction of the America Invents Act, which are to improve patent quality.

Reexamination

Under current practice, an IPR petitioner who does not invalidate all challenged claims at the PTAB may, in addition to the IPR proceeding, bring a conventional ex parte reexamination proceeding. The PREVAIL Act would make this more difficult in several ways.

The act would add the same one-year time bar applicable to IPR to ex parte reexamination.

The PREVAIL Act also attempts to close the door on subsequent reexamination challenges that try to fix a deficiency in the petitioner's argument that the PTAB identified in a prior IPR — e.g., in an institution or final written decision.

Some early critiques of the PREVAIL Act have noted that the proposed limits on the use of ex parte reexamination proceedings do not account for patents containing larger claim sets or patents that involve complex subject matter that currently may seek to use reexamination in addition to IPR, especially in view of the IPR petition word limit issue discussed above.

Reassignment of the Judicial Panel

Under the existing AIA statutory framework, the same three administrative patent judges who decide whether to institute a trial also preside over the trial proceedings.

Under the PREVAIL Act, a PTAB administrative patent judge "who participates in the decision to institute an inter partes review or a post-grant review of a patent shall be ineligible to hear the review."

Proponents of this proposed change have argued that it ensures that the trial panel gives a fresh look at the unpatentability evidence that was evaluated by the panel instituting trial.

Opponents of this proposed change have argued that requiring a different panel that is not familiar with the institution decision's reasoning would create inefficiencies and slow the decision process, potentially frustrating one of the key drivers for IPR procedure — i.e., having an efficient mechanism for resolving questions of unpatentability.

Additional Time After Institution

The PREVAIL Act would amend Title 35 of the U.S. Code, Section 314 to potentially lengthen the time between institution and a final written decision by adding a new subsection (e) setting forth a 45-day rehearing period for institution decisions that can be extended for good cause not more than an additional 30 days.

The act would also add a 90-day period for director review of a final written decision that can be extended for good cause not more than an additional 60 days.

Finally, any decision remanded to the PTAB by the U.S. Court of Appeals for Federal Circuit must be decided in a 120-day period that can be extended for good cause not more than an additional 60 days.

Potentially Expands Discovery as to Real Parties in Interest

The PREVAIL Act would explicitly modify Title 35 of the U.S. Code, Section 316(a)(5) to add a category of named discovery: The director must promulgate regulations to address discovery practice relating to "evidence identifying the real parties in interest of the petitioner."

How The PREVAIL Act Would Change Other Aspects of the PTAB

While not likely to have an immediate impact on practitioners, the PREVAIL Act makes additional changes to strengthen the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

Ends Diversion of Certain User Fees Collected for Use by Unrelated Federal Agencies

The act would stop the practice of diverting fees collected by the USPTO for use by unrelated federal agencies. Proponents of the bill point out that since 2010, over $400 million dollars in user fees have been diverted from the USPTO that could have been used instead for "timely and quality examination."

The PREVAIL Act seeks to have the USPTO keep collected user fees for its own use.

Establishes a Code of Conduct for Members of the PTAB

The PREVAIL Act would mandate the director to establish a code of conduct and consider in its creation the Code of Conduct for United States Judges "and how the provisions of that [judicial] Code of Conduct may apply."

How the PREVAIL Act Compares to Other PTAB Reform Attempts

The PREVAIL Act would differ from prior legislative revisions in several key ways. Set out below:

At the very least, the PREVAIL Act presents a set of interesting changes that should get practitioners and their clients thinking about ways in which their future litigation strategies before the PTAB could change.

The opinions expressed are those of the authors on the date noted above and do not necessarily reflect the views of Fish & Richardson P.C., any other of its lawyers, its clients, or any of its or their respective affiliates. This post is for general information purposes only and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice. No attorney-client relationship is formed.