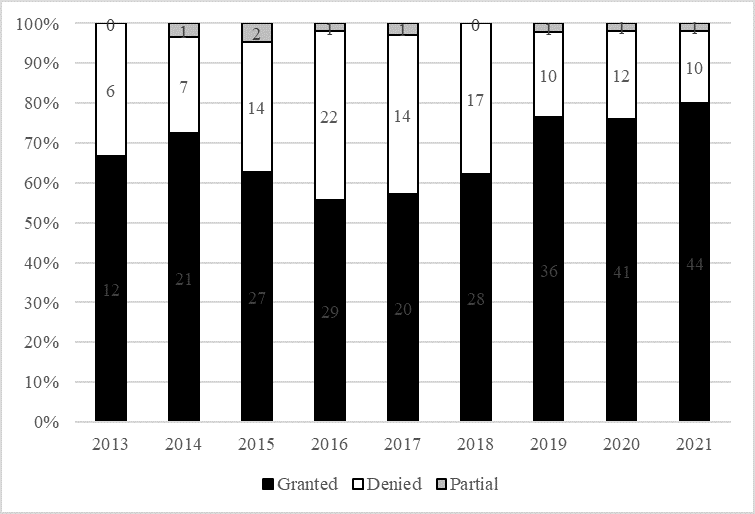

Fig. 2 Motion Success for Stays Pending IPR – All Districts Excluding Delaware

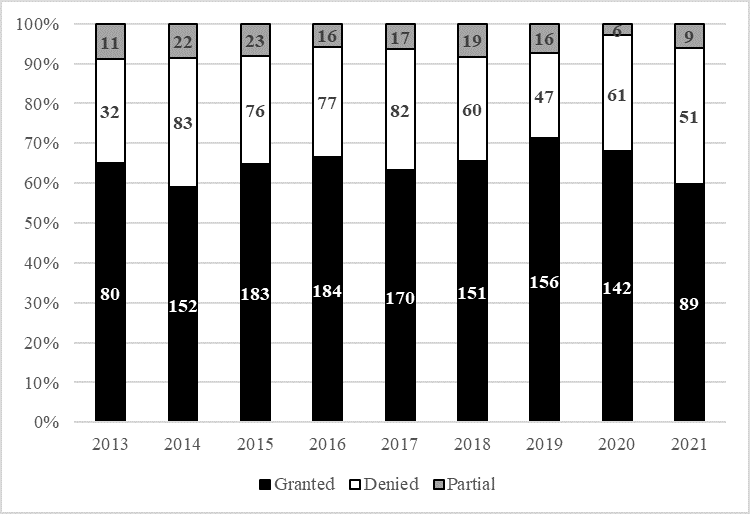

The District of Delaware's 80% grant rate for stays pending IPR includes motions to stay that were filed before the IPR was instituted. When those early motions are removed, it becomes clear that the District of Delaware routinely grants motions to stay pending IPR after institution the percentage of stays granted rises to 88%, 91%, and 90% for 2019, 2020, and 2021, respectively.3 Thus, the likelihood of receiving a stay increases significantly if the petitioner has secured IPR institution before seeking a stay.4

But Obtaining a Stay, Even After Institution of the IPR, is Not Guaranteed

While the District of Delaware has routinely granted stays pending IPR after the IPR has been instituted, stays are not automatic. In each case, the court will consider three factors: (1) whether granting the stay will simplify the issues for trial; (2) the status of the litigation, particularly whether discovery is complete and a trial date has been set; and (3) whether a stay would cause the non-movant to suffer undue prejudice from any delay, or allow the movant to gain a clear tactical advantage." See, e.g., Toshiba Samsung Storage Tech. Korea Corp. v. LG Elecs., Inc., 193 F.Supp.3d 345, 348 (D. Del. 2016). Moreover, as Magistrate Judge Hall explained recently, these factors are not meant to be dispositive but serve as guidelines for the court in reaching a decision:

[T]his Court typically considers three factors...Those factors are meant to help the Court weigh the competing interests of the parties. Although the three-factor test informs the Court's inquiry, it is not a prescriptive template. The Court retains the prerogative to balance considerations beyond those captured in the three-factor test; and ultimately, the Court must decide stay requests on a case-by-case basis.

3Shape A/S v. Align Tech., Inc., C.A. No. 1-18-cv-00886-LPS-JLH, D.I. 368 at 29 (D. Del. Mar. 5, 2021).

Consideration of a stay is a fact-specific inquiry, and unique circumstances may weigh against a stay, even when IPR has already been instituted. For example, if the IPR will resolve only a small fraction of an ongoing case, that fact can lead to denial of a stay motion, either after institution, or even, in a rare circumstance, after issuance of a final written decision. See, e.g., ON Semiconductor Corp. et al. v. Power Integrations, Inc., C.A. No. 1-17-cv-00247-LPS, D.I. 236 at 16-18 (D. Del. Aug. 2, 2019) (denying partial stay after institution of four IPRs challenging two of the eight asserted patents); Sunoco Partners Marketing & Terminals LP v. Powder Springs Logistics, LLC et al., C.A. 1-17-cv-01390-LPS, D.I. 547 at 15-16 (D. Del. June 9, 2020) (denying partial stay after final written decision finding all claims in two of the five asserted patents unpatentable). Additionally, a party's delay in filing a motion to stay following institution may also weigh against granting a stay. See, e.g., 3G Licensing, SA et al. v. LG Elecs., Inc. et al., C.A. No. 1-17-cv-00085-LPS-CJB, D.I. 240 (D. Del. Apr. 16, 2019) (stay denied where defendants waited over seven months after institution to move for stay). Finally, as another example, in 3Shape A/S, Judge Hall denied a stay even though the IPR had been instituted because Judge Stark had already ordered the case, one of several between the same two parties, to be tried second and a stay would jeopardize that trial. See C.A. No. 1-18-cv-00886-LPS-JLH, D.I. 368 at 30-32. facts of each case should therefore be carefully considered in assessing the likelihood of a stay.

Grant of a Stay Is Unlikely To Reduce Overall Time In Court

Assuming a party does receive a stay, how does the imposition of a stay affect the overall timing of district court litigation in Delaware? Only two cases in Delaware have gone to trial following a full stay and resolution of a co-pending IPR, under very different circumstances.

First, in Wasica Finance GmbH et al. v. Schrader International Inc., C.A. No. 1-13-cv-01353, Defendant Schrader filed its IPR early in the case, just a month after an amended complaint was filed and before any scheduling order had been entered. Shortly thereafter, the parties stipulated to a stay.5 The PTAB instituted and ultimately found sixteen claims unpatentable and five claims patentable.6 Schrader appealed to the Federal Circuit, and the parties agreed to maintain the stay during the pendency of the appeal.7 The Federal Circuit affirmed the Board's findings on all but one claim, which it reversed and found unpatentable.8 The case came back to the district court when the stay was lifted in November 2017.9 The case proceeded to trial 27 months after the stay was lifted, in February 2020, just before the COVID-19 pandemic. On February 14, 2020, a jury returned a verdict in favor of Plaintiff Wasica on all counts and awarded $31.2m in damages. Excluding the period of the stay, the case was pending for 34 months, just four months longer than the average time to a jury trial from complaint in Delaware.10

Second, in Parallel Networks Licensing LLC v. Microsoft Corporation, C.A. No. 1-13-cv-02073, Defendant Microsoft filed four IPRs challenging the asserted patents on the last day of the statutory one-year deadline imposed by the AIA.11 The PTAB instituted and consolidated the proceedings. Microsoft filed a motion to stay the proceedings through the conclusion of the IPRs at the PTAB, approximately one month before opening expert reports were due.12 While Plaintiff Parallel Networks initially opposed the stay, at oral argument it relented, taking the position that, if the Court would not bifurcate estopped art from non-estopped art at trial, then a stay was appropriate.13 The Court found that, because the trial date was one month after the patents were set to expire, and two months before the PTAB was scheduled to issue its decision, a stay was warranted.14 The PTAB then held all challenged claims patentable15, and the district court litigation restarted in August 2016.16 The case proceeded to trial nearly nine months later, with a jury returning a verdict of no infringement in favor of Microsoft. All told, the case was pending for just over 30 months, excluding the time the case was stayed.

While these two cases represent only a very small sample size, they suggest that staying a case pending the resolution of an IPR in Delaware may result in little difference from the standard 30-month schedule normally seen in Delaware if the IPR does not resolve the parties' dispute. A party faced with the possibility of a stay should therefore be aware that, if the petitioner does not prevail before the PTAB, and the case returns back to the district court, any contemplated efficiencies expected in the post-IPR litigation simply may not materialize, depending on the circumstances of the case. In other words, while the IPR may have resulted in some narrowing of the issues in the litigation, the parties may ultimately not save much in the way of either expense or time to reach a final judgment. The efficiencies of the IPR process as an alternative to litigation only reliably materialize when a petitioner can prevail and render the parallel litigation moot or, in theory, if the number of asserted claims and/or patents at issue in the parallel suit can be meaningfully reduced. Regardless, IPRs (and the resulting stays in litigation) continue to be a well-used strategy in the District of Delaware for resolving patent disputes.

[1] 77 F. Reg. 48680-01 (Aug. 14, 2012).

[2] A stay is referred to as "partial" if the case in the district court proceeded on some asserted claims or patents during the pendency of the IPR.

[3] All statistics cited herein were compiled through using Docket Navigator's analytics and are current as of February 27, 2022.

[4] See, e.g., compare Analog Devices, Inc. v. Xilinx, Inc., C.A. No. 1-19-cv-02225-RGA, D.I. 101 (Aug. 19, 2020) (denying stay pre-institution), with D.I. 197 (Feb. 22, 2021) (granting stay post-institution); compare Boston Scientific Corp. et al. v. Nevro Corp., C.A. No. 1-16-cv-01163-GMS, D.I. 127 (Nov. 29, 2017) (denying stay pre-institution), with D.I. 244 (June 15, 2018) (granting stay post-institution); compare Speyside Med., LLC v. Medtronic CoreValve LLC et al., C.A. No. 1-20-cv-00361-CJB, D.I. 108 (May 20, 2021) (denying stay pre-institution) with D.I. 155 (Sept. 30, 2021) (granting stay post-institution); Targus Int'l LLC v. Victorinox Swiss Army, Inc., C.A. No. 1-20-cv-00464-RGA, D.I. 146 (Apr. 26, 2021) (denying stay pre-institution) with D.I. 199 (July 14, 2021) (granting stay post-institution).

[5] See 1-13-cv-01353, D.I. 18 (unopposed motion to stay granted).

[6] See Schrader Int'l Inc. v. Wasica GmbH, IPR2014-00295, Paper No. 30 (July 22, 2015); see also Continental Auto. Sys., Inc. v. Wasica Finance GmbH, IPR2014-00295, Paper No. 41 (June 17, 2015) (IPR filed by defendant in parallel litigation that settled in 2018).

[7] See 1-13-cv-01353, D.I. 22 (joint status report requesting stay be maintained through appeal).

[8] See Wasica Finance GmbH v. Continental Auto. Sys., C.A. 15-2078, D.I. 63 (Apr. 4, 2017) (consolidated with Wasica Finance GmbH v. Schrader-Bridgeport, C.A. 15-2093).

[9] See 1-13-cv-01353, D.I. 26 (order lifting stay).

[10] According to Docket Navigator's analytics, the average time to a jury trial in the District of Delaware from 2017 to present was 30 months. The average time to a bench trial over that same patent lit period was 33 months.

[11] IPR2015-00483; IPR2015-00484; IPR2015-00485; IPR2015-00486

[12] See 1-13-cv-02073, D.I. 232 (opening brief re motion to stay).

[13] See 1-13-cv-02073, D.I. 265 at 1-2 (Court's order granting stay, citing to Transcript of 10/8/15 hearing at 45).

[14] Id. at 2.

[15] IPR2015-00483, Paper No. 81 at 26 (Aug. 11, 2016) (consolidated with IPR2015-00484); IPR2015-00485, Paper No. 81 at 25 (Aug. 11, 2016) (consolidated with IPR2015-00486).

[16] See 1-13-cv-02073, D.I. 268 (order lifting stay).