Article

Hatch-Waxman 2023 Year in Review

Fish & Richardson

Authors

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Associate

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

Nearly 40 years ago, Congress signed into law the Hatch-Waxman Act, balancing the need for lower cost prescription drugs and protection of pharmaceutical innovations. For both branded and generic drug developers, the Hatch-Waxman legal landscape continues to evolve through decisions by courts, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). 2023 was no exception, with major developments in the law of enablement, patent term adjustments/patent term extension, and obviousness, as well as increased regulatory scrutiny of the pharmaceutical industry. Read about these developments below or watch our webinar recording.

Trends in Hatch-Waxman litigation

Over the past 15 years, the number of Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) District Court litigations filed peaked in 2014 and 2015. While there was another smaller peak in cases in 2017, case filings generally have declined since then. It now appears that the decline may be plateauing and that the number of cases filed is returning to the early-2010s level. (See Figure 1 below.)

Figure 1: number of ANDA cases filed

The trends in the number of ANDAs submitted to FDA versus ANDA cases filed have followed one another fairly closely, although there has been a general decline in the number of ANDAs submitted in recent years. There are several possible explanations for this dip. First, the trend of consolidation in the generic industry over the past few years means that fewer generic drugmakers may be filing ANDAs. Second, generic drugmakers may be focusing on more profitable and complex generic drugs. Third, both branded and generic drugmakers may be shifting some of their research and development into biologics and biosimilars. We will continue to monitor this trend and compare the number of ANDAs filed against similar data in the biologics and biosimilars space. (See Figure 2 below.)

Figure 2: ANDA cases filed vs. ANDAs submitted

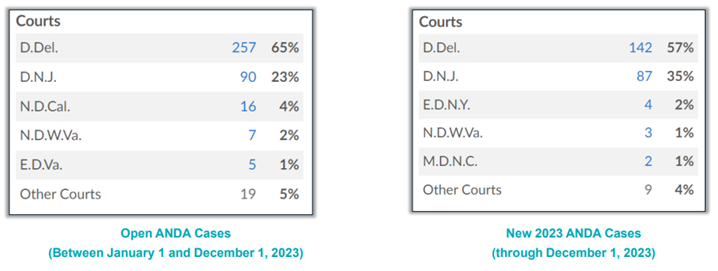

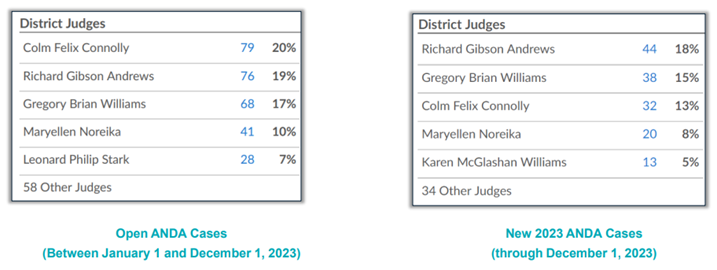

Over the past six years, both the Supreme Court and the Federal Circuit issued cases that many believed would greatly influence venue in Hatch-Waxman cases, most notable among those cases being TC Heartland, LLC v. Kraft Foods Group Brands, LLC, 581 U.S. 258 (2017) and Celgene Corp. v. Mylan Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 17 F.4th 1111 (2021). However, several years of data show that these cases have failed to buck the longstanding trend of the Districts of Delaware and New Jersey remaining strongholds for Hatch-Waxman litigation, which will likely continue for 2024. In 2023, there was a slight uptick of cases filed in New Jersey compared to Delaware, although it is unclear if this is merely an anomaly or the beginning of a long-term trend. (See Figure 3 below.)

Figure 3: busiest venues for ANDA cases in 2023

Given that the District of Delaware receives a majority of ANDA case filings, it should come as no surprise that the judges of that district are the busiest judges for ANDA cases. (See Figure 4 below.)

Figure 4: busiest judges for ANDA cases

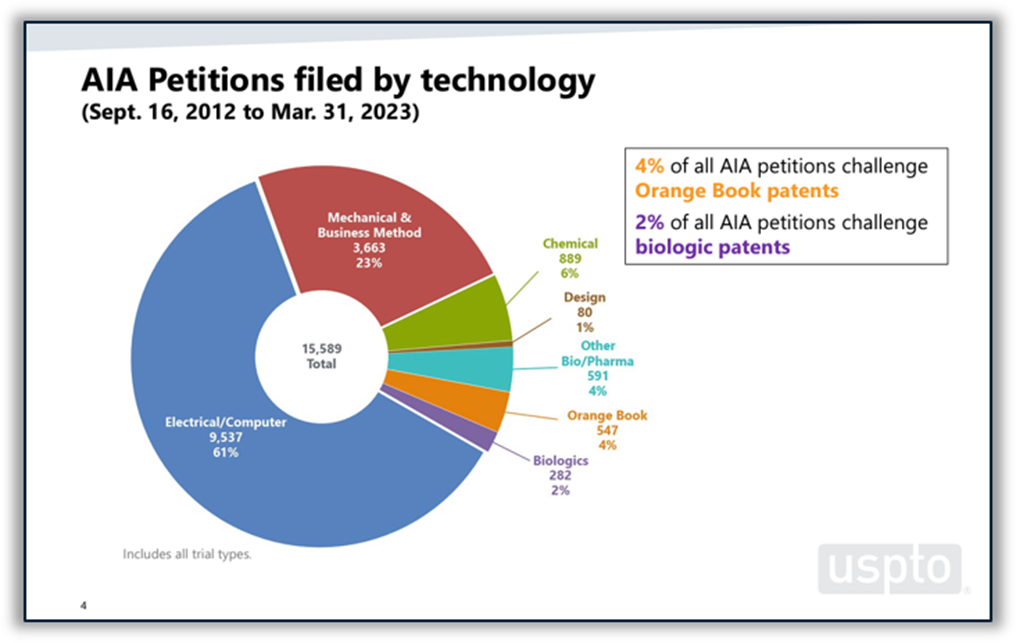

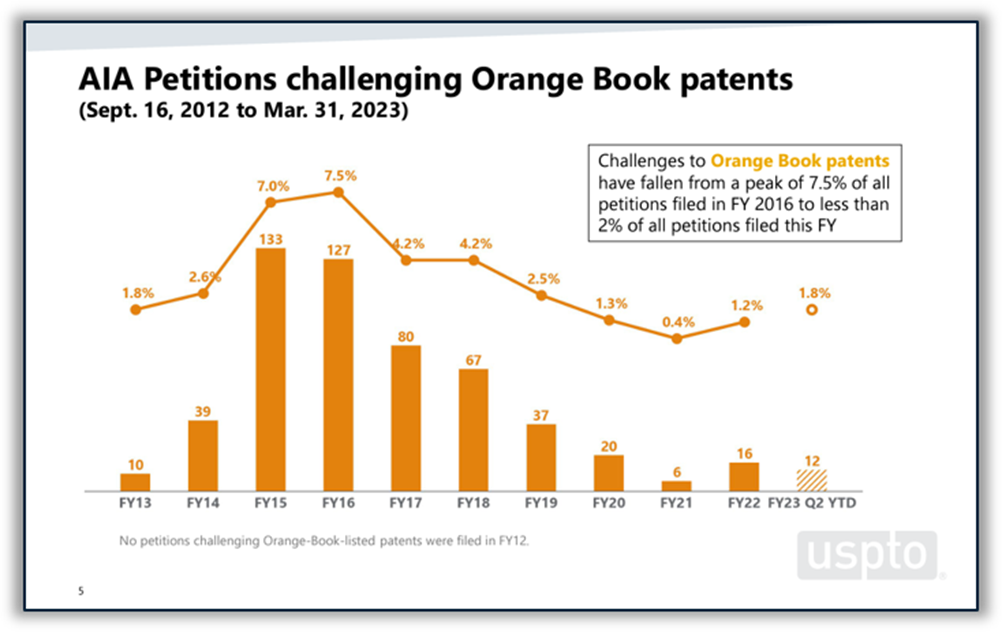

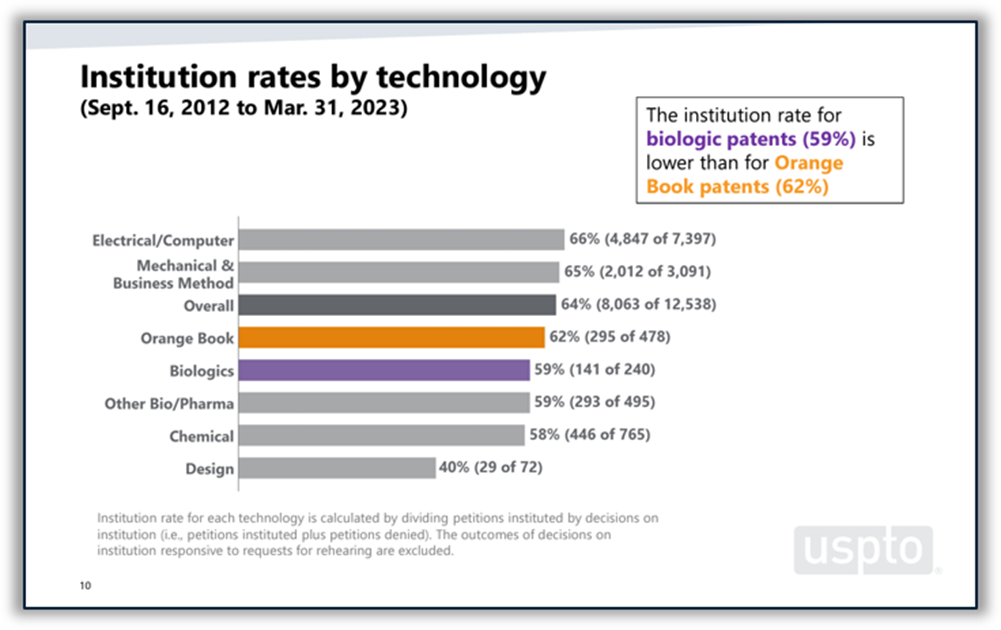

Disputes between branded and generic drugmakers often begin based on what patents a branded drugmaker lists in FDA’s Orange Book as covering the branded drug. U.S. District Courts are not the only forums in which Orange Book patents are disputed. According to the USPTO’s 2023 Orange Book patent/biologic patent study, 4% of all America Invents Act petitions filed at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) between 2012 and the end of Q2 of FY 2023 challenged Orange Book patents. Post-grant challenges to Orange Book patents peaked in 2015 and 2016 and have been on a downward trend since then, although there was a slight increase in the number of challenges filed in 2022 and through Q2 of FY 2023. The institution rate for Orange Book patents over the period studied was 62%, which places it roughly in the middle of the pack among all technologies and near the PTAB average of 64%. (See Figure 5 below.)

Figure 5: Orange Book patents at the PTAB

Case narrowing

With so many ANDA cases filed in so few districts, a question arises as to how the judges of those districts are handling their heavy caseloads. Beginning in 2022, and continuing with greater force through 2023, a trend arose of judges putting stricter limits on the number of claims and defenses that ANDA litigants can advance, as well as enforcing those limits earlier in their cases. One of the best examples of this trend is Judge Connolly amending his scheduling order for Hatch-Waxman cases in 2022. As part of the amendment, Judge Connolly now limits branded drugmaker plaintiffs to no more than 10 claims of any one patent and no more than 32 claims in total against any one defendant. Judge Connolly similarly has limited generic drugmaker defendants to no more than 12 prior art references for any one patent and no more than 30 prior art references in total.

Other judges in the District of Delaware have followed Judge Connolly’s lead. In Hope Medical Enterprises Inc. v. Accord Healthcare Inc., No. 22-00978-RGA, D.I. 36 (D. Del. Mar. 31, 2023), Judge Andrews noted that a narrowing to 32 total claims was “reasonable” and directed further reduction in advance of a pretrial order. Judge Andrews also ordered a narrowing to 40 claims and seven invalidity arguments per claim before opening expert reports and a subsequent narrowing to seven claims and three invalidity arguments per claim before a pretrial order in Exeltis USA, Inc. v. Lupin Ltd., No. 22-00434-RGA, D.I. 199 (D. Del. July 31, 2023). In Veloxis Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Accord Healthcare, Inc., No. 22-00909-JDW, D.I. 40 (D. Del. Jan. 31, 2023), Judge Wolson, sitting by designation, not only ordered early narrowing of asserted claims (10 claims per patent and 50 total claims) and invalidity contentions (12 references or combinations per patent and 50 total references or combinations) in advance of the Markman hearing, but further required reducing the number of claims and prior art references by half about a month after issuance of the claim construction order.

This trend indicates that parties on both sides should come prepared with their best claims and defenses early on, with the expectation that their claims and defenses will continue to narrow throughout their cases. However, to date, litigants are still filing ANDA cases asserting numerous patents. For example, in AbbVie, Inc. v. Hetero USA, Inc., No. 23-1332-MN (D. Del. filed Nov. 20, 2023), AbbVie asserted 34 patents and 136 counts of infringement against multiple generic challengers. It will be interesting to see whether other judges and courts adopt Judge Connolly’s approach to early case narrowing.

Interplay of patent term adjustment and obviousness-type double patenting

The patent statute creates two mechanisms that allow for the term of a patent to be extended to compensate for delays in government review. The patent term adjustment (PTA), governed by 35 U.S.C. Section 154, allows for an extension of patent term due to delays in prosecution at the USPTO. These delays are based on delays in the examination of a specific patent and the adjustment is applied to that specific patent only. The patent term extension (PTE), governed by 35 U.S.C. Section 156, allows for an extension of patent term due to delays in regulatory review for products subject to review by FDA or the United States Department of Agriculture. It is added to one patent of the patentee’s choice covering a specific product whose marketing approval was delayed.

Disputes often arise where PTA and PTE brush up against obviousness-type double patenting concerns. Obviousness-type double patenting is a judicially created doctrine that is intended to prevent a patentee from obtaining an extension of a patent for the same invention as another patent it has already obtained. The Federal Circuit previously addressed the interplay of PTE and obviousness-type double patenting in 2018 in Novartis AG v. Ezra Ventures, LLC, 909 F.3d 1367 (Fed. Cir. 2018). There, the court held that obviousness-type double patenting does not invalidate validly obtained PTE under Section 156. Id. at 1373. The court explained that applying obviousness-type double patenting to a patent that had received PTE would allow a judge-made doctrine to cut off a statutorily authorized time extension, which the court declined to do. Id. at 1375.

This year, the court addressed the interplay of PTA and obviousness-type double patenting in In re Cellect, LLC, 81 F.4th 1216 (Fed. Cir. 2023). There, Cellect had five issued patents that claimed devices with image sensors. Id. at 1219. Originally, all five patents had the same expiration date, but because of delays in prosecution, PTA was added to four of the patents. Id. Cellect did not file terminal disclaimers, as the patent examiner did not raise the issue of obviousness-type double patenting during prosecution. See id. at 1219-20. Ex parte reexamination of the four patents that received PTA was requested, asserting that the patents were unpatentable based on obviousness-type double patenting. Id. at 1220. During ex parte reexamination, the PTAB found that the claims of the patents that received PTA were invalid due to obviousness-type double patenting based on a network of invalidating references that traced back to the patent in the family that did not receive PTA. Id.

The Federal Circuit focused its analysis on the text of the statutes governing PTA and PTE. Id. at 1223-29. Although Section 154 (the PTA statute) and Section 156 (the PTE statute) both state that the term of the patent “shall” be extended, rendering such extensions non-discretionary, the court found that the primary difference between the two statutory schemes is that Section 154 includes language that states “[n]o patent the term of which has been disclaimed beyond a specified date may be adjusted under this section beyond the expiration date specified in the disclaimer,” while Section 156 does not include language expressly excluding patents in which a terminal disclaimer has been filed from benefitting from PTE. Id. at 1226-27. Because patent applicants almost always file terminal disclaimers to overcome obviousness-type double patenting rejections, terminal disclaimers and obviousness-type double patenting are inextricably linked. Id. at 1228.

Based on this statutory comparison, the court held that PTA and PTE should be treated differently when determining whether claims are unpatentable under obvious-type double patenting because the two mechanisms serve distinct purposes. Id. at 1227. PTE extends the overall patent term for a single invention due to regulatory delays in product approval; extending one patent beyond another is not contrary to the congressional intent of PTE. Id. PTA extends the term of a single patent due to delays in prosecution; as such, the underlying concerns meant to be addressed by obviousness-type double patenting still apply in such cases. Id.

The court concluded that when evaluating obviousness-type double patenting for patents that have received PTE, the expiration date for the analysis is the expiration date before the PTE has been added. For patents that have received PTA, the expiration date used for the obviousness-type double patenting analysis is the date after the PTA has been added, regardless of whether or not a terminal disclaimer is required or has been filed. Accordingly, the court found all asserted claims of the patents at issue invalid due to obviousness-type double patenting.

Following the decision, Cellect has petitioned for rehearing en banc, and numerous players in the pharmaceutical industry and organizations filed amicus briefs regarding the rehearing. There are concerns in the industry, especially for small companies, that the decision may discourage filing follow-on patents that claim additional aspects of inventions for fear of invalidating earlier-filed patents. In Allergan USA, Inc. v. MSN Laboratories Private Ltd., No. 19-1727-RGA, 2023 WL 6295496 (D. Del. Sept. 27, 2023), applying the Cellect ruling for the first time, Judge Andrews applied a bright line to the obviousness-type double patenting analysis, and did not consider equitable concerns, such as whether the patent was “first filed, first issued.” We will monitor and report on further developments in this area.

Anticipation, obviousness, and overlapping ranges

The concept of overlapping ranges and their impact on anticipation and obviousness challenges often comes up in ANDA cases. An “overlapping range” refers to an overlap between the claimed range and a range disclosed in a prior art reference. For example, a patent that claims a pH range of 4-7 would overlap with a prior art reference that discloses a pH range of 5-9.

In 2023, the Federal Circuit revisited the analysis of overlapping ranges in the context of anticipation and obviousness in UCB, Inc. v. Actavis Labs UT, Inc., 65 F.4th 679 (Fed. Cir. Apr. 12, 2023). There, branded drugmaker UCB developed and sold a transdermal patch marketed as Neupro® for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease and restless leg syndrome. Id. at 684; UCB, Inc. v. Actavis Lab'ys UT, Inc., No. CV 19-474-KAJ, 2021 WL 1880993 at *1 (D. Del. Mar. 26, 2021). The active ingredient of Neupro® is rotigotine, which is formulated with an inactive ingredient (polyvinylpyrrolidone or “PVP”) that is meant to stabilize rotigotine. Id. A key factor in this case was the weight ratio of rotigotine to PVP; UCB marketed an initial version of Neupro® with a 9:2 ratio and, later, a reformulated version with a 9:4 ratio. UCB, 65 F.4th at 684–85. UCB owned Orange Book-listed patents covering both versions. Id. The patents on the original version (known as the “Muller patents”) eventually expired and were used as prior art. Id. at 685.

The dispute between the parties began when Actavis submitted an ANDA for a generic version of Neupro® in 2013. Id. UCB sued, alleging infringement of one of the Muller patents. Id. After a successful bench trial in 2017, UCB obtained an injunction preventing approval of Actavis’ ANDA. Id. In 2019, UCB again sued Actavis, alleging that the 2013 ANDA infringed a new patent UCB had obtained in 2018 (the ’589 patent). Id. at 685–86. The limitation in dispute was a range “wherein the weight ratio of rotigotine free base to [PVP] is in a range from about 9:4 to about 9:6.” Id. at 685. Actavis argued that the Muller patents described an identical invention to that of the ’589 patent because the Muller patents described weight ratios of 9:1.5 to 9.5. UCB, No. CV 19-474-KAJ, 2021 WL 1880993 at *2. Actavis further contended that persons of ordinary skill in the art would know to increase the weight ratio of PVP to add stability to the patch given the known stabilizing effects of PVP on amorphous rotigotine. Id. Actavis also argued that others were dissuaded from competing with UCB in the Neupro® market given a cohort of blocking patents negating any potential objective indicia of non-obviousness. Id.

The District of Delaware agreed with Actavis. On anticipation, the court applied the “at once envisage” framework articulated in Kennametal, Inc. v. Ingersoll Cutting Tool Co., 780 F.3d 1376, 1381 (Fed. Cir. 2015) and found that the Muller patents anticipated all of the asserted claims. UCB, 65 F.4th at 686. On obviousness, the court found that the asserted claims would have been obvious in view of multiple prior art references, including the Muller patents. Id.

On appeal, the Federal Circuit split with the District of Delaware on its analysis of overlapping ranges for anticipation. Judge Stoll, writing for the panel, found that the District Court erred in applying Kennametal and the “immediately envisage” line of cases to its evaluation of anticipation of overlapping ranges. Id. at 687. The Court held that the Ineos standard is more appropriate in such cases. Id. (citing Ineos USA LLC v. Berry Plastics Corp., 783 F.3d 865, 869 (Fed. Cir. 2015)). That is, “[o]nce the patent challenger has established, through overlapping ranges, its prima facie case of anticipation, ‘the court must evaluate whether the patentee has established that the claimed range is critical to the operability of the claimed invention.’” Id. (quoting Genentech, Inc. v. Hospira, Inc., 946 F.3d 1333, 1338 (Fed. Cir. 2020) (quoting Ineos, 783 F.3d at 871)).

On obviousness, the Federal Circuit affirmed the District Court’s finding that the claimed range of weight ratios of rotigotine to PVP overlap with that disclosed in the Muller patents and that UCB failed to rebut this prima facie case of obviousness. UCB, 65 F.4th at 689–97. In particular, the court found that “no cataclysmic change” in the product rendered the prior art unusable. Id. at 691. Further, the court found that there were no unexpected results because the results obtained by the alleged invention and those in the Muller patents are “similar in kind . . . [and] with similar levels of stability (i.e., lack of crystallization).” Id. at 694–95. Lastly, the court found there was no commercial success because the Muller patents operated as blocking patents dissuading competitors from developing a rotigotine transdermal patch. Id. at 696–97.

The message from this decision is two-fold. On the one hand, the Federal Circuit decision may be seen to favor patent owners by limiting application of Kennametal and the “at once envisage” rubric, permitting patent owners to avoid anticipation by establishing that “the claimed range is critical to the operability of the claimed invention.” See id. at 687. On the other hand, the decision reinforces the defense of “blocking patents,” which can make it more difficult to support the non-obviousness of later issued patents based on objective indicia of non-obviousness, like commercial success. See id. at 696–97. We will monitor if and how District Courts apply this decision going forward.

The state of enablement post-Amgen

In May 2023, the Supreme Court decided Amgen, Inc. v. Sanofi, 598 U.S. 594 (2023), a dispute concerning functional genus claims for antibodies. There, the claims of the patents at issue covered “the entire genus” of antibodies that (1) “bind to specific amino acid residues on PCSK9,” and (2) “block PCSK9 from binding to [LDL receptors].” Id. at 599. The specification identified 26 example antibodies that perform these functions and contained two methods that scientists could use to make other antibodies that perform the functions. Id. at 602–03. The Court held that Amgen failed to enable all that it had claimed under Section 112(a) even allowing for a reasonable degree of experimentation. Id. at 613. The unanimous opinion states, “[i]f a patent claims an entire class of processes, machines, manufactures, or compositions of matter, the patent’s specification must enable a person skilled in the art to make and use the entire class.” Id. at 610.

Since then, a line of cases from lower courts have applied and extended the reasoning of Amgen to claims involving antibodies, methods of treatment, and compositions.

The Federal Circuit and the District of Massachusetts both addressed enablement in the context of antibodies and reached similar conclusions. In Baxalta, Inc. v. Genentech, Inc., 81 F.4th 1362 (Fed. Cir. 2023), the genus claims were to an antibody or antibody fragments that “binds Factor IX or Factor IXa and increases the procoagulant activity of Factor IXa.” Id. at 1366. The court found that the facts of this case were “materially indistinguishable from those in Amgen,” where only 11 amino acid sequences were disclosed for “millions of potential candidate antibodies” with the claimed function. Id. It was undisputed in this case that “to practice the full scope of the claimed invention, skilled artisans must make candidate antibodies and screen them to determine which ones perform the claimed functions,” which the court found was “the definition of trial and error.” Id.

In Teva Pharmaceuticals International GmbH v. Eli Lilly & Co., No. 18-cv-12029-ADB, 2023 WL 6282898 (D. Mass. Sept. 26, 2023), the asserted claims that “cover[ed] the entire functionally-defined genus of humanized anti-CGRP antagonistic antibodies” were found to be invalid for lack of enablement where the specification disclosed only one covered antibody while the actual number of antibodies that could potentially antagonize CGRP was “mind-bogglingly large” and “not knowable.” Id. at *22, 24. The claims did not identify any amino acid sequence or unique structure for a covered antibody, which the court found would prevent a person of skill in the art from predicting whether an antibody would satisfy the claims based on its amino acid sequence or structure. As such, the court found that “these facts amount to nothing more than a ‘roadmap’ for a ‘trial and error’ process to identify and make antibodies within the scope of the Asserted Claims.” Id. at *22.

The post-Amgen enablement cases are not limited to antibody claims. The claims at issue in Medytox, Inc. v. Galderma S.A., 71 F.4th 990 (Fed. Cir. 2023), were directed to a method of treatment that included a responder rate limit that the court construed as a range of 50-100%, and the court treated this range as analogous to a genus. The specification contained “at most three examples of responder rates above 50% at 16 weeks: 52%, 61% and 62%.” Id. at *10. Relying on the reasoning of Amgen that “the more one claims, the more one must enable,” the court found that the claim at issue was not enabled because a person of skill in the art “would not have been able to achieve responder rates higher than the limited examples provided in the specification” based on the techniques disclosed. Id.

Practitioners, however, should not read into these cases a bright line rule that any requirement for testing will render a claim not enabled under Amgen. In Orexo AB v. Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., 2023 WL 4492095 (D.N.J., August 11, 2023), the composition claim at issue required two different components that were provided in the form of particles in which one set of particles was separate from the other when mixed. The specification disclosed dry mixing of the two components to achieve this, but Sun had developed its own proprietary method to achieve the same outcome. Sun argued that the claims were not enabled because the specification did not teach a person of skill in the art how to use its own process to make separate microparticles. Id. at *23. The court found that Amgen was inapposite because this case involved a single drug composition, not an entire genus, thereby declining to extend the scope of Amgen.

As the cases above demonstrate, practitioners should pay particular attention to the scope of their claims post-Amgen. Generally, the more predictability there is in the underlying art, the more likely it is that experimentation will be “reasonable.” Courts were particularly concerned with potential monopolization of the genus at issue, so practitioners should ensure that they are drawing fair boundaries around what they are claiming. Furthermore, the guidance in the specification must be something more than a recipe for trial and error or a “roadmap” to pass muster under Amgen. Perhaps most significantly, recent post-Amgen decisions establish that the reasoning of Amgen extends beyond antibody claims.

U.S. government agency developments and their impact on Hatch-Waxman litigants

Recently, the USPTO and FDA each commented on recent collaboration efforts aimed at reducing inconsistent statements before these agencies and promoting generic competition.

On February 23, 2023, the USPTO held a webinar to discuss the collaboration initiatives it launched in 2022 focusing on the duties of disclosure and reasonable inquiry. The USPTO discussed its belief that this policy is useful regardless of whether Belcher Pharmaceuticals, LLC v. Hospira (Fed. Cir. 2021) is an outlier, as the USPTO has not seen a deluge of cases like Belcher to date. In any case, webinar presenters discussed key factors for patent holders to consider in ensuring they make consistent statements in submissions to USPTO and FDA. These considerations include understanding both the scope of the claimed invention and the timing of pending applications and submissions to FDA. The presenters also discussed considerations related to ex-U.S. regulatory submissions. Specifically, regulatory submissions with data from clinical trials conducted overseas that are the basis for an approval outside the U.S. would have to be provided to the USPTO if such information would be considered material for any U.S. pending application. Another key takeaway relates to Paragraph IV certifications. Determining whether a Paragraph IV certification served on a patent owner by an ANDA applicant would be material to a patent application depends on several circumstances, including whether: (1) there is a pending application that relates to the same active ingredient and there are claims of unpatentability in the Paragraph IV certification; (2) the basis for unpatentability relates to a presently claimed invention that is currently being prosecuted; and (3) the information in that Paragraph IV certification relates to the patentability of an application that is currently pending at the USPTO.

On October 19, 2023, FDA participated in a Food and Drug Law Institute Webinar on USPTO-FDA collaboration. The FDA Regulatory Counsel presenting stated that FDA does not intend to be involved in substantive patent dispute issues, but the agency is exploring what they can do within the confines of the Orange Book Transparency Act. The Senior Lead Administrative Patent Judge of the PTAB presenting suggested that there are many mixed questions in regulatory and statutory interpretation that are within the purview of FDA and in patent law and indicated that they would take FDA’s lead and collaborate when necessary.

Another of the most important 2023 regulatory developments affecting Hatch-Waxman litigants was the Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC’s) increased involvement as a government stakeholder in pharmaceutical legal disputes, as evidenced by its increasing interest in Orange Book patents. In September, the FTC released a policy statement in which it claimed that improper Orange Book listings harm competition in the pharmaceutical market by delaying generic product entry. In the Commission’s view, branded drugmakers’ improper listing of patents in the Orange Book to take advantage of FDA’s automatic 30-month stay of approval for generic competitors constitutes an unfair method of competition within Section 5 of the FTC Act. The policy statement warned that the Commission would scrutinize Orange Book listings and that any parties found to have improperly listed patents may be subject to enforcement actions.

In November, the Commission challenged more than 100 patents it alleged to be improperly listed using FDA’s regulatory dispute process. Upon receiving a dispute notice, FDA must notify the New Drug Application holder, who then has 30 days to either amend or withdraw the listing or certify under penalty of perjury that the listings comply with the applicable statutory and regulatory requirements. While the Commission’s most recent enforcement actions are limited to disputing Orange Book patents using FDA’s process, the Commission notified the identified patent holders that it retains the right to pursue additional remedies, including Section 5 investigations. As of the date of this publication, at least three of the targeted companies have removed patent listings from the Orange Book.

To navigate these new developments within government agencies, stakeholders can take certain actions to avoid risks and unexpected developments, including: (1) identifying the FDA regulatory milestones and submissions for which an inquiry could be reasonable under the particular circumstances; (2) reviewing USPTO and FDA submissions for material inconsistencies; (3) drafting internal procedures for coordinating patent prosecution and regulatory functions to help meet the USPTO’s clarified duties and potential FTC scrutiny; (4) conducting due diligence reviews related to the USPTO duties for acquisitions or sales of life sciences entities and products; and (5) establishing internal procedures to help minimize waiver of the privilege protecting attorney-client communications involving the foregoing. Early case assessment addressing these issues is often valuable before launching Hatch-Waxman litigation.

The opinions expressed are those of the authors on the date noted above and do not necessarily reflect the views of Fish & Richardson P.C., any other of its lawyers, its clients, or any of its or their respective affiliates. This post is for general information purposes only and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice. No attorney-client relationship is formed.