Article

Patent Fee-Shifting Often Leaves Prevailing Parties Unpaid

Authors

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Associate

Principal Adam Shartzer and Associate Josh Carrigan authored Expert Analysis for Law360 examining a fee-shifting statute for patent cases that allows prevailing parties to recover their reasonable attorney fees in exceptional patent infringement cases. The underlying policy rationale is that awarding fees in exceptional cases where sanctions were necessary deters the “improper bringing of clearly unwarranted suits.” But is that policy rationale truly being achieved? The results might surprise some. This article details the authors’ study of Section 285 attorney fees awards against patentees from 2017 through 2022 and describes two potential reform efforts toward ensuring that prevailing parties receive Section 285 fee awards.

Read the full article at Law360.

A fee-shifting statute for patent cases under Title 35 of the U.S. Code, Section 285, allows a prevailing party to seek recovery of its reasonable attorney fees.[1]

A district court has wide latitude to determine whether a case is exceptional, and thus deserving of a fee award to the prevailing party.[2]

Attorney fees may be awarded against a patentee when, for example, the infringement claim was particularly weak. On the other hand, fees may be awarded against a defendant for the unreasonable manner in which the case was defended.

Motions for fees under Section 285 are far from a sure bet. Since the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2014 Octane Fitness LLC v. ICON Health & Fitness Inc. decision, the success rate on Section 285 motions is approximately 30%.

That is a fairly low percentage if one presumes that a fee motion is not filed in every case and is instead limited to those where a prevailing party strongly felt the case was exceptional.

This low success rate likely reflects the discretion district courts apply in awarding fees to those limited circumstances where, according to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in the 1990 Badalamenti v. Dunham’s Inc. decision, “it would be grossly unjust,” for the winner to also bear its fees.[3]

One such circumstance is when a patentee brings infringement claims that are clearly unjustified. The policy behind Section 285 addresses this problem by providing defendants an avenue to recoup fees expended on a clearly unwarranted suit.[4]

But is that policy rationale truly being achieved through recouped fees? To find out, we conducted a survey and study of Section 285 attorney fees awards against patentees from June 2017 through June 2022.

The results might surprise some: 36% of those fee awards went unpaid or unsettled, amounting to uncollected fees of $12 million. From that figure, one might surmise that a prevailing party has a roughly two-in-three chance of getting paid.

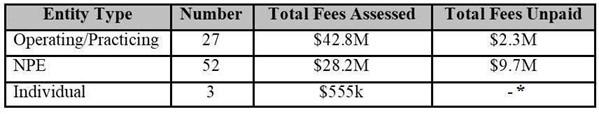

The data reveals, however, that the likelihood of collecting the full fee award is hardly that generous. And significantly, when fees are assessed against a nonpracticing entity, or NPE, the likelihood of never being paid increases dramatically as contrasted with a practicing entity.

NPEs account for almost 90% of the cases where fees were assessed, but never paid.

In recent years, NPEs have walked away from paying at least $9.7 million in ordered fees. That number stands to rise significantly higher — by as much as an additional $6.5 million — with recent, pending fee awards assessed against NPEs that are not yet final and remain subject to appeal.

The policy behind Section 285 is undermined when attorney fees awards go unpaid.

This article details our study and describes two potential reform efforts toward ensuring that prevailing parties receive payment on fee awards.

Study Structure

We located 82 cases involving a Section 285 fee award against a patentee between June 2017 and June 2022. Through docket analysis and anonymized survey data through counsel of record, we determined the outcome of 58 Section 285 fee award cases.[5]

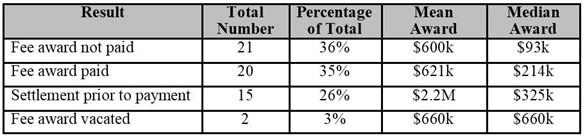

Awards ranged from $3,000 to $13.3 million. The findings from those 58 cases are summarized in the table below.

To determine whether the type of patentee affected how often fees were paid, we placed the patentees into three categories: operating or practicing entity, nonperforming, and individual.

For category placement, we relied on data collected and analyzed in the Stanford Law School NPE Litigation Database.[6] The database places entities into 13 categories.[7]

Because we do not require the same level of granularity as the database, we combined Stanford’s classifications into the smaller set of broad categories noted above.

Results

As the chart above illustrates, in fee award cases over the last five years, NPEs were assessed fees in 52 cases, or 63% of all fee awards. That NPEs make up the majority of all fee awards is not surprising, as this result mirrors the data regarding the numbers of cases filed over the past five years.

As Unified Patents reports, approximately 59% of cases in the past five years were filed by NPEs.[8] Our data also suggests that NPEs are not assessed fee awards at a rate significantly higher than operating entities.

Simply put, the courts are fairly even-handed at assessing fees in exceptional cases at a rate that roughly mirrors case filing rates by patentee type.

While the correlation in the rate at which fee awards are assessed is reassuring, the payment rate data tells a different story. First, a party awarded Section 285 fees has a on-in-three chance of never receiving those fees.

Second, NPEs are far more likely to never pay the fees ordered against them as compared to other entities. In fact, of the 21 cases in which a fee award was ordered but not paid, 18, or 86%, were cases filed by an NPE.

In other words, the likelihood of never getting paid increases dramatically — from 16% to 47% — when the patentee is an NPE versus a practicing entity.

As between fee awards that were paid versus fee awards that were not paid, our results showed consistency in terms of the amount of the fee awards assessed.

For example, with fee awards that were paid, the average amount awarded was $621,000. That figure is within approximately 3% of the average value of the fee awards that went unpaid: $600,000.

The consistency of this data suggests that the amount of the fee award has little to no impact on whether an entity will pay. Instead, it appears that the structure and nature of the patentee’s business holds an outsized impact on the likelihood of payment. This finding is consistent with the observations from our data indicating that NPEs account for 86% of fee awards that were not paid.

Our study indicates that NPEs can be elusive entities to pursue for Section 285 fee awards collection. In one instance, the 2019 Max Sound Corp. v. Google LLC decision in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, fees of $820,000 were assessed against Max Sound.[9]

Based upon docket entries in the case, Max Sound avoided payment for so long that Google LLC successfully moved the court to amend the fees judgment to include Max Sound’s officers as judgment debtors.[10]

As of the date of publication, however, the fees remain unpaid. Instead, the patentee used a separate entity to sue again on the same patent.[11]

Fee nonpayment tells only part of the story. When nonpayment cases are combined with cases that settled after the fee award — e.g., some consideration was exchanged, but presumably less than the full fee award — a prevailing party has a 62% overall chance of receiving something less than the full award. Oftentimes, it is much less.

Consider Energy Innovation Co. v. NCR Corp. in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Georgia, which was settled shortly after a 2020 fee award against an NPE.[12]

NCR accepted an assignment of the asserted patent as a substitute for the $110,000 attorney fees award.[13] Settlement occurred after the court ordered Energy Innovation to show cause why it failed to comply with the court’s fee order[14] and NCR moved the court to enforce the judgment.[15]

These case examples highlight a couple of vexing questions that are difficult to answer.

First, why are NPEs so much less likely to pay fee awards?

One possible explanation is that the NPEs that do not pay the ordered fees are underfunded entities — often limited liability companies — created for purposes of patent assertion.

The LLC form is then used to shield investors, parent entities or third-party litigation funders from liability if fees are assessed against the NPE. Another possible explanation for uncollected fees is that the collections process is simply too difficult and expensive to pursue. Beyond the uncollected fee award lies a morass of collections laws that vary from state to state.

This lack of uniformity in collections laws makes collections efforts difficult and expensive, which contributes to fee awards being abandoned by prevailing parties.

Second, what can be done to increase the likelihood that patentees pay on Section 285 fee awards?

Rule reform may provide an answer. In recent years, at least two different rule-based approaches have been proposed or implemented in various forms, both having a likelihood of improving the payment rate of fee awards in patent cases. The first type of reform requires that a bond be posted for the anticipated cost of litigation.

Starting in 2014, several states implemented new laws that would impose a bonding requirement in certain situations. Vermont, Idaho, and North Carolina were among the earliest implementers of reform measures. In Idaho, for example, the Legislature adopted a bonding requirement to address bad faith patent infringement assertions.[16]

In Micron Technology Inc. v. Longhorn IP LLC, Micron asserted claims against Longhorn in Idaho state court in June, requesting a $15 million bond under the Idaho statute. Longhorn continues to oppose paying a bond, attacking the propriety of Idaho’s law, including for federal preemption and overbreadth, among other substantive and procedural arguments.

Idaho Attorney General Lawrence Wasden moved to intervene, announcing his intent to defend the constitutionality of Idaho’s statute regarding bad faith patent infringement assertions.

The second type of reform provides a more subtle avenue for change by amending the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure to require that parties disclose financial backing early in the action. One such proposed amendment to Rule 26(a)(1)(A) would require disclosure of third-party investments in litigation.[17]

With this proposal, prevailing defendants would at least know the full scope of entities or individuals responsible for funding the exceptional litigation and against whom they might seek to enforce the attorney fees award.[18] This reform would have a similar — though less direct — effect to a bonding requirement.

As it stands, there is no effective way for a defendant — or the court — to confirm the entities that have a financial interest in the outcome of the litigation. Indeed, the Max Sound saga discussed above is a prime example of the muddy waters that surround patent ownership and financial interests.

At least one judge, Chief U.S. District Judge Colm F. Connolly of the U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware, has issued a standing order that addresses disclosure of financial interests in litigation.[19] Though Judge Connolly’s order withstood a recent mandamus challenge by a purported patentee with ties to a prolific patent litigation funder, IP Edge,[20] that order may be subject to future challenges in the months to come.[21]

Conclusion

Section 285 is an effective tool to deter frivolous patent infringement actions only if parties can actually collect the awarded fees. As shown by our study data, even when attorney fees are awarded, it is far from certain — or even likely — that a party will collect the full amount of those fees.

It remains highly unlikely that a fee award will be collected if the fees are assessed against a NPE. The structure of the NPE and its business appears to be a contributing factor to non-payment of fee awards.

Parties seeking to collect fees awarded under Section 285, or judgment creditors — particularly fees awarded against NPEs, or judgment debtors — should not rest easy hoping for a payment once the judgment is final and nonappealable.

In those situations, the judgment is collectible after 30 days and prevailing parties should ensure that any appeal of the fee award is at least bonded by the judgment debtor.

Absent bonding by the judgment debtor, a prevailing party should consider serving any discovery allowed by applicable state rules to understand the structure and funding status of the NPE. Depending on the state, post-judgment interrogatories, requests for production and a deposition — in the form of a judgment debtor exam — are often allowed.

The information gained through this discovery will guide further collection efforts. And, as with the Max Sound case discussed earlier, understanding the structure of the NPE and its operations is crucial to any future attempt to pierce the corporate veil for purposes of collecting on the Section 285 fee award.

Though the bonding and rule reforms discussed earlier might improve the chances of collecting a fee award, they remain the exception to the rule. If bonding requirements were more uniformly adopted, uncollected section 285 fee awards would surely be reduced.

If the Federal Rules were amended to require disclosure of third party funding agreements, prevailing parties in patent cases would have a financially viable target to pursue for collection.

Ultimately, both reforms may be necessary to more effectively achieve Section 285’s policy purpose of deterring, as the Federal Circuit wrote in the 2000 Automated Business Cos. Inc. v. NEC America Inc. decision: “improper bringing of clearly unwarranted suits.”[22]

Payal Patel, a student at George Washington University Law School, contributed to this article.

[1] 35 U.S.C. §285.

[2] Octane Fitness, LLC v. ICON Health & Fitness, Inc., 572 U.S. 545, 554 (2014) (“[A]n

‘exceptional’ case is simply one that stands out from others with respect to the substantive strength of a party’s litigating position (considering both the governing law and the facts of the case) or the unreasonable manner in which the case was litigated.”).

[3] Badalamenti v. Dunham’s, Inc., 896 F.2d 1359, 1364 (Fed. Cir. 1990) (quoting J.P. Stevens Co. v. Lex Tex Ltd., 822 F.2d 1047, 1052 (Fed. Cir. 1987)) (emphasis in original, internal quotation marks omitted).

[4] Automated Bus. Cos. v. NEC Am., Inc., 202 F.3d 1353, 1354 (Fed. Cir. 2000) (Section 285 addresses a policy rationale of awarding fees in exceptional cases where sanctions are necessary to deter the “improper bringing of clearly unwarranted suits.”) (quoting Mathis v. Spears, 857 F.2d 749, 753–54 (Fed. Cir. 1988)).

[5] As of this publication, 10 cases were still pending. In another 14 cases, we were unable to determine whether the fee award was paid.

[6] See npe.law.standford.edu.

[7] For a complete description of Stanford’s thirteen categories, see Shawn P. Miller, Who’s Suing Us? Decoding Patent Plaintiffs Since 2000 with the Stanford NPE Litigation Dataset, 21 Stan. Tech. L. Rev. 235, 244-246 (2018). By name and number, the Stanford categories are: (1) acquired patents; (2) university heritage or tie; (3) failed startup; (4) corporate heritage; (5) individual-inventor-started company; (6) university/government/non-profit; (7) pre-product startup; (8) product company; (9) individual; (10) undetermined; (11) industry consortium; (12) IP subsidiary of product company; and (13) corporate-inventor-started company. Id. (noting the Database considers all but category 8 to be non-practicing entities). Categories 2-4, 6, 7, 10-11, and 13 were not represented in the cases we analyzed. Thus, in line with Stanford’s analysis, we designated categories 1, 5, and 12 as NPE, category 9 as Individual, and category 8 as Operating/Practicing.

[8] Unified Patents, 2021 Patent Dispute Report: Year in Review, Fig. 6 (Jan. 3,

2022), https://www.unifiedpatents.com/insights/2022/1/3/2021-patent-dispute-report-year-in-review (noting five-year district court NPE-related litigation average of 59%).

[9] 5-14-cv-04412 (N.D. Cal.).

[10] See Max Sound Corp. v. Google Inc., 5-14-cv-04412 (N.D. Cal.), Dkt. No. 235 (Order granting Google’s motion to amend judgment, adding Max Sound’s officers).

[11] See Vedanti Licensing Ltd., LLC v. Google LLC, 21-cv-01643-SK (N.D. Cal.), Dkt. No. 1 (complaint for patent infringement of U.S. Patent No. 7,974,339), Dkt. No. 87 at 1-2

(discussing previous actions involving ‘339 patent).

[12] 1-18-cv-03919 (N.D. Ga.).

[13] Id., Dkt. No. 83 (noting satisfaction of judgment via transfer of asserted patent).

[14] Id., Dkt. No. 78 (Motion to Enforce Clerk’s Judgment).

[15] Id., Dkt. No. 77 (Order to Show Cause), Dkt. No. 78 (noting Energy Innovation lacks cash or liquidity to pay the fee award).

[16] See Idaho Code section 48-1701, et seq.

[17] Letter from U.S. Chamber Institute for Legal Reform, the American Insurance Association, the American Tort Reform Association, Lawyers for Civil Justice, and

the National Association of Manufacturers to Jonathan C. Rose, Secretary of the Committee on Rules of Practice and Procedure of the United States Courts re Proposed Amendment to Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(a)(1)(A), available at http://www.lfcj.com/uploads/3/8/0/5/38050985/final_version_-_tplf_disclosure_letter_4_9_2014.pdf.

[18] Id. at pg. 6 (“Fourth, the disclosure of TPLF arrangements would be important information to have on the record in the event that a court determines it should impose sanctions or other costs.”).

[19] Standing Order Regarding Third-Party Litigation Funding Arrangements (Apr. 2022), available

at https://www.ded.uscourts.gov/sites/ded/files/Standing%20Order%20Regarding%20Third-Party%20Litigation%20Funding.pdf.

[20] See In re Nimitz Techs. LLC, No. 23-103 (Fed. Cir. Nov. 17, 2022) (order staying challenged trial court order); see also Pet. for Writ of Mandamus, In re Nimitz Techs. LLC, Case No. 23-103 (Fed. Cir. 2022); Judge Connolly’s New Standing Order Requiring Disclosure Behind Patent Assertion Entities Is Showing It Has Teeth, Aug. 24, 2022, available at https://www.fr.com/judge-connollys-new-standing-order-requiring-disclosure-behind-patent-assertion-entities-is-showing-it-has-teeth/.

[21] In re Nimitz Techs. LLC, No. 2023-103, Doc. No. 44, Order Denying Mandamus Petition (Fed. Cir. Dec. 8, 2022),

available at https://cafc.uscourts.gov/opinions-orders/23-103.ORDER.12-8- 2022_2045190.pdf.

[22] Automated Bus. Cos. v. NEC Am., Inc., 202 F.3d 1353, 1354 (Fed. Cir. 2000) (quoting Mathis v. Spears, 857 F.2d 749, 753–54 (Fed. Cir. 1988)).

The opinions expressed are those of the authors on the date noted above and do not necessarily reflect the views of Fish & Richardson P.C., any other of its lawyers, its clients, or any of its or their respective affiliates. This post is for general information purposes only and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice. No attorney-client relationship is formed.