Blog

Two Recent Trademark Decisions Provide Ammunition for Trademark Owners Who Receive Improper Specimen Refusals for Service Marks

Fish & Richardson

Authors

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

In the past few years, many trademark practitioners have noticed an increase in the number of rejections for trademark specimens - the documents that applicants submit to the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) to prove that they are using the mark in U.S. commerce. Two recent decisions from the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) should make the process much easier, particularly where a mark is for software or technical services.

In the U.S., trademark rights arise from use of a mark in commerce (i.e., in connection with the sale of goods or services). What constitutes "use in commerce" depends on the goods/services. Generally, goods require sales of the actual, trademarked products. In contrast, with services, use in commerce can be based on sales or advertising of the trademarked services. In either case, the applicant must submit a specimen that shows:

- The mark in substantially the same form as it appears in the application;

- The goods/services (or a textual description of the goods/services); and

- Some indication that the goods or services are currently available for purchase.

As part of its efforts to cut down on fraudulent trademark applications, the USPTO has steadily increased its scrutiny of specimens over the past few years. The impact has been experienced primarily by domestic, U.S. applicants, particularly where (1) the mark is used for goods and related services or (2) the mark is used for downloadable and non-downloadable software.

In re Pitney Bowes, Inc., 125 U.S.P.Q.2d 1417 (TTAB 2018) dealt with the first scenario. The applicant (PB) is a multinational company that (among other things) offers postage meters, mailing equipment, and shipping services. In January 2015, PB applied to register the following logo for various Class 39 mailing and shipping services:

The TTAB did agree with the examining attorney that the specimen raised some reasonable doubt as to whether PB was, in fact, providing shipping services. However, "[the] explanation of the specimen and how [PB] provides the outsourced mailing services referenced on the specimen resolved the ambiguity, and the refusal should not have been maintained." In other words, an explanation from the applicant on how it provides services can be sufficient to overcome a specimen refusal for a service mark.

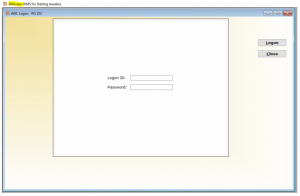

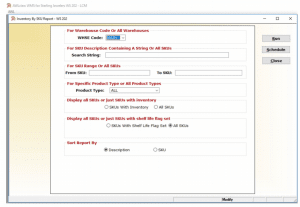

In re Minerva Associates, Inc., 125 USPQ2d 1634 (TTAB 2018) dealt with the second scenario, where an applicant seeks registration of a mark for downloadable and non-downloadable (SaaS) software. The USPTO treats downloadable software as a Class 9 good, and non-downloadable software as a Class 42 service, even though the two versions of the software may be functionally identical. In Minerva, the applicant applied to register the word AWLVIEW as a trademark for inventory management software in Classes 9 and 42, submitting the following screenshots of the login page and search screens from the applicant's software as the specimen of use:

These two cases highlight an important practice tip - pick up the phone and call the Examining Attorney to clarify any questions or misunderstandings there may be about the goods/services and the specimens that have been submitted (and if that does not work, reach out to the Managing Attorney.) In both of these cases where the TMEP clearly supported the Applicant's position, a call with the Examining Attorney would likely have avoided the effort and expense of a TTAB proceeding.

The opinions expressed are those of the authors on the date noted above and do not necessarily reflect the views of Fish & Richardson P.C., any other of its lawyers, its clients, or any of its or their respective affiliates. This post is for general information purposes only and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice. No attorney-client relationship is formed.